Street names are political weapons. They produce memories, attachment and intimacy—all while often sneakily distorting history.

Saint Louis, Senegal. Image credit Goodwines via Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

June 18, 1940 is well known throughout Francophonie: it is the date of Charles de Gaulle’s famous speech calling for resistance against France’s occupation by Nazi Germany and its ally, the Vichy regime. The then-governor of Chad, Felix Eboué, was one of the first political leaders to support de Gaulle; he proclaimed his support from Brazzaville, the capital of “Free France” between 1940 and 1943. To this day, in Dakar and Bamako, as in all the metropole’s cities, at least one street name references the event. On the other hand, who remembers Lamine Senghor’s scathing indictment of French colonialism—which he urged to “destroy and replace by the union of free peoples”—before the League Against Imperialism in Brussels on February 11, 1927? Two public addresses calling for resistance to servitude: one proudly displayed around the empire, the other pushed into oblivion.

Recent movements like Rhodes Must Fall, Faidherbe Must Fall, and Black Lives Matter have forced us all to face the political nature of odonyms (identifying names given to public communication routes or edifices), carriers of a selected and selective memory. If a street, a square, a bridge, a train station, or a university proudly carries a name, it is because someone decided it would. In Senegal, historian Khadim Ndiaye insists that “it was when the power of the gunboats defeated all the resistance fighters that Faidherbe’s statue was erected in the middle of Saint-Louis as a sign of rejoicing.” “Lat Dior was assassinated in 1886,” he adds, “and the statue was inaugurated on March 20, 1887 . . . to show the greatness of the metropole.”

To live on Edward Colston Street, Léopold II Avenue, or Jean-Baptiste Colbert Boulevard is to adopt, through time, a geographical identity based on that given name. One starts becoming accustomed to its sound, as it takes a life of its own; generating scenes of endless discussions around tea, of traffic jams on the way home from work, of bargaining with the local shopkeeper. Everything from the bakery, pharmacy, and police station to the hotel, ATM, and gas station bear its shadow. A name that produces memories, attachment, intimacy—all while sneakily erasing its backstory. Rhodes? Ah, my college years! Pike? Good times we had around that statue! Columbus? What a lovely park that square had!

Odonyms have the power of not only negating history but also distorting memory. May 8, 1945 is synonymous with both liberation and carnage. In Europe, the date marks the surrender of Germany and the victory of the Allied powers. In Algeria, for having dared to demand their liberation from the colonial yoke during the parade celebrating the end of the war, thousands (probably tens of thousands) of Algerians were killed in the cities of Sétif, Guelma, and Kherrata. Two memories face each other between the May 8, 1945 bus stop in Paris or the May 8, 1945 square in Lyon on the one hand, and the May 8, 1945 airport in Sétif or the May 8, 1945 university in Guelma on the other. Moreover, the “liberation” commemorated through the avenue running alongside Dakar’s port celebrates that of France in 1944–1945, not Senegal’s. This “liberation” occurred when the country was still a colony, its children subject to the Code de l’indigénat (Native Code), and its soldiers—at the Thiaroye camp, on December 1, 1944—coldly executed in the hundreds for demanding their compensation for fighting in the French army.

As sociologist Alioune Sall Paloma argues, “naming is an act of power.” Odonyms can thus equally be used by officials to seize historical legitimacy over a popular figure or event. Despite being attacked throughout his life, everyone in Senegal now seems to erect multifaceted thinker Cheikh Anta Diop as an unquestionable reference. How is it, then, that the country’s largest university—that happens to bear his name, on an avenue named after him, which now also hosts a statue of him—does not teach his groundbreaking work? Or that, in February 2020, five high schools in the country were renamed after authors Aminata Sow Fall and Cheikh Hamidou Kane, filmmaker Ousmane Sembène, sculptor Ousmane Sow, and revolutionary leader Amath Dansokho, all while artists barely manage to survive from their work and the political principles these namesakes stood by are today systematically scorned?

There is also a lot to say about many heads of states’ obsession with “going down in history.” In Cameroon, the largest football stadium in the country, built for the 2021 African Cup of Nations, honors current lifetime president Paul Biya. In Côte d’Ivoire, after only two years in office, Alassane Ouattara gave his name to the university of Bouaké. In Senegal, under the impetus of his brother—also involved in politics and at the center of a 2019 multibillion-dollar oil scandal—President Macky Sall now has a high school named after him in the capital’s suburb.

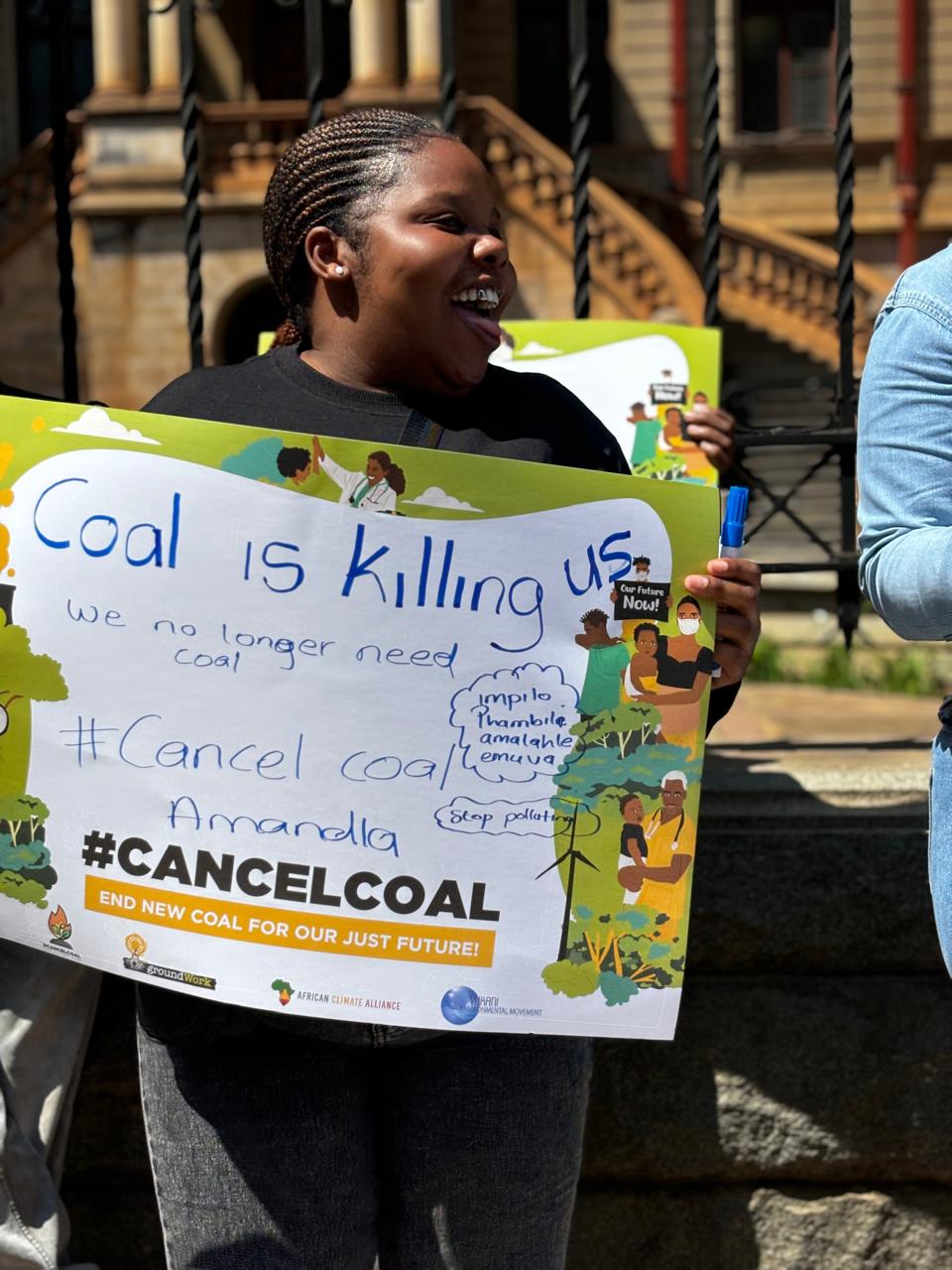

Decolonization—a term increasingly abused and gutted of its meaning—supposes the conservation and promotion of Africa’s multidimensional heritage. Material heritage is decolonized through, in particular, the rehabilitation of emblematic sites and buildings and the restitution of its cultural heritage trapped in Western museums. Decolonizing immaterial heritage requires the repatriation of audiovisual archives seized by foreign funds and a thorough refoundation of odonyms. Finally, human heritage is decolonized by concrete support to artists and young creative souls, so that no one can claim, when it will be too late: “They did their best, despite the obstacles. If only we had uplifted them during their lifetime.”